Charité team identifies brain network that triggers tics

Berlin, 19.01.2022 – A research team at the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin has identified a neuronal network that is responsible for the development of tic disorders. Stimulation of this network by deep brain stimulation – known as brain pacing – has led to symptom relief in people with Tourette’s syndrome. The findings, published in the journal Brain*, could lay the groundwork for better treatment of severe tic disorders.

Tics are usually short movements or vocalisations that are often repeated in rapid succession and without any apparent reference to the current situation. Strong blinking or head spinning, for example, are motor tics, while clearing the throat or whistling are vocal tics. In many cases, the disorder is accompanied by other behavioural problems such as anxiety and compulsions, ADHD or depression, and social exclusion of those affected is a frequent consequence. One of the best-known tic disorders is Tourette’s syndrome, in which various vocal and motor tics occur together. Tic disorders usually appear in childhood. It is estimated that up to four percent of all children are affected, and about one child in a hundred meets the diagnostic criteria for Tourette’s syndrome. Often, but not always, the symptoms subside in adulthood at the latest.

Little is known about how tics actually develop in the brain. “In recent years, neurological research has identified different areas of the brain that play a role in tics,” says the study’s final author Dr Andreas Horn. He is head of an Emmy Noether junior research group on network-based brain stimulation, based both at the Department of Neurology with Experimental Neurology at Charité Campus Mitte and at Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham & Women’s Hospital within Harvard Medical School in Boston, USA. Dr Horn explains: “However, it remained unclear: Which of these brain areas trigger the tics? Which ones are active instead to compensate for faulty processes? We have now been able to show that it is not a single brain region that causes the behavioural disorders. Tics are instead due to malfunctions in a network of different areas in the brain.”

For the study, the research team first used already published case descriptions of patients with an extremely rare cause of tic disorders: Their symptoms were due to acquired damage to the brain substance – for example, due to a stroke or accident. In these patients, tics are therefore clearly caused by the injured area of the brain. The researchers found 22 such cases in the literature and mapped in detail where the injury to the brain substance was located and with which other brain areas this location would normally be connected via nerve fibres. For this connectivity analysis, they used an “average circuit diagram” of the human brain that had been created over years of work at the Department of Neurology with Experimental Neurology in cooperation with Harvard Medical School based on brain scans of over 1,000 healthy people.

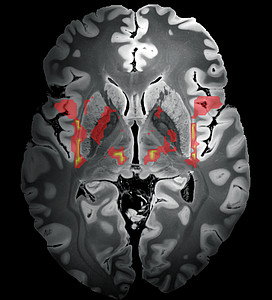

The research group was thus able to show that the brain damage of the patients – despite different localisation in the brain – was almost all part of a common nerve plexus. This network included the most diverse areas of the brain, namely the insular cortex, the cingulate gyrus, the striatum, the globus pallidus internus, the thalamus and the cerebellum. Bassam Al-Fatly, one of the two first authors of the study from the Department of Neurology with Experimental Neurology, explains: “These structures are distributed practically throughout the entire brain and have a wide variety of functions, from controlling motor skills to processing emotions. They have all been discussed in the past as possible triggers for tics, but no clear proof has been found so far and a direct connection between these structures was also not known. Now we know that these brain areas form a network and may actually be the cause of tic disorders.”

The research team showed that the now identified nerve network is also relevant for the treatment of “classic” tics by analysing 30 patients with Tourette’s syndrome who had been implanted with brain pacemakers with differently placed electrodes at three different European treatment centres. Such deep brain stimulation is currently used in particularly severe cases when behavioural therapy and medication approaches are not sufficiently effective. The Berlin scientists used brain scans to determine for each of the 30 Tourette’s patients where exactly the electrodes of the brain pacemaker had been positioned and whether they had stimulated the tic-triggering neuronal network. In fact, the more precisely the electrodes stimulated the tic network, the greater the reduction in symptoms.

“People with severe tic disorders therefore seem to benefit most when deep brain stimulation targets the tic network,” says private lecturer Dr Christos Ganos, first author of the study and senior medical director of the outpatient clinic for tic disorders at the Department of Neurology with Experimental Neurology. The Freigeist Fellow of the Volkswagen Foundation emphasises: “In future, we will incorporate this new finding into the treatment of our patients by taking the tic network into account when implanting the brain pacemaker. We hope that in this way we will be able to alleviate the really high level of suffering for those affected even better, in order to enable them to lead a self-determined and socially fulfilled life as far as possible.”

*Ganos C, Al-Fatly B et al. A neural network for tics: insights from causal brain lesions and deep brain stimulation. Brain (2022), doi: 10.1093/brain/awac009

Charité outpatient clinic for tic disorders

The Department of Neurology with Experimental Neurology has been running an outpatient clinic for tic disorders at the Charité Campus Mitte since 2017. It offers those affected comprehensive counselling and treatment based on current neurological, psychiatric and behavioural psychological findings and also takes into account additional existing disorders. In addition to medication and behavioural therapy, the therapeutic offers also include deep brain stimulation. The outpatient clinic is run by Prof. Dr. Andrea Kühn and private lecturer Dr. Christos Ganos.

Caption

The areas marked in colour in this brain scan are part of the neuronal network that can trigger tics. © Charité | Bassam Al-Fatly