Neurological symptoms apparently not a consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection of the brain

Berlin, 16.02.2024

It is still not conclusively clear how neurological symptoms are caused by COVID-19. Is it because SARS-CoV-2 infects the brain? Or are the symptoms a result of inflammation in the rest of the body? A study by Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin now provides evidence in favour of the latter theory. It was published today in the journal Nature Neuroscience*.

Headaches, memory problems and fatigue are just some of the neurological impairments that can occur during a coronavirus infection and continue beyond. Early on in the pandemic, researchers suspected that a direct infection of the brain could be the cause. “We also initially assumed this hypothesis. However, there is no clear evidence to date that the coronavirus can persist or even multiply in the brain,” explains Dr Helena Radbruch, head of the Chronic Neuroinflammation research group at Charité’s Institute of Neuropathology. “This would require, for example, the detection of intact virus particles in the brain. Instead, the evidence that the coronavirus could affect the brain comes from indirect test methods and is therefore not entirely conclusive.”

According to a second hypothesis, the neurological symptoms would instead be a kind of side effect of the strong immune response with which the body defends itself against the virus. Past studies had also provided evidence for this. The current Charité study now supports this theory, with comprehensive molecular biological and anatomical results from autopsy examinations.

No signs of direct infection of the brain

For the study, the research team analysed different areas of the brains of 21 people who had died in hospital, mostly in intensive care, due to a severe coronavirus infection. For comparison, they used 9 patients who had succumbed to other diseases after intensive care treatment. The researchers first checked whether the tissue showed any visible changes and searched for evidence of the coronavirus. They then analysed genes and proteins in detail to determine which processes were taking place in individual cells.

Like other research teams, the Charité scientists were able to detect the genetic material of the coronavirus in the brain in some cases. “However, we have not found any SARS-CoV-2-infected nerve cells,” emphasises Helena Radbruch. “We assume that immune cells have taken up the virus in the body and then migrated to the brain. They still carry the virus, but it does not infect brain cells. The coronavirus has therefore infected other cells in the body, but not the brain.”

Brain reacts to inflammation in the body

Nevertheless, the researchers observed that the molecular processes in some cells of the brain were conspicuously altered in those affected by COVID-19: For example, the cells ramped up the so-called interferon signalling pathway, which is typically activated in the course of a viral infection. “Some nerve cells apparently react to the inflammation in the rest of the body,” says Prof Christian Conrad, head of the Intelligent Imaging working group at the Berlin Institute of Health at Charité (BIH). He led the study together with Helena Radbruch. “This molecular reaction could well explain the neurological symptoms of COVID-19 sufferers. For example, messenger substances released by these cells in the brain stem can cause fatigue. This is because the brain stem contains cell groups that control drive, motivation and mood.”

The reactive nerve cells were mainly found in the so-called nuclei of the vagus nerve, i.e. nerve cells that are located in the brain stem and whose extensions reach into organs such as the lungs, intestines and heart. “In simple terms, we interpret our data to mean that the vagus nerve ‘senses’ the inflammatory reaction in different organs of the body and reacts to it in the brain stem – without any real infection of brain tissue,” summarises Helena Radbruch. “In this way, the inflammation is transferred from the body to the brain, so to speak, which can disrupt its function.”

Temporary reaction

The nerve cells only react temporarily to the inflammation, as a comparison of people who died either during the acute coronavirus infection or at least two weeks later showed. Most pronounced during the acute illness, the molecular changes normalised again afterwards – at least in the vast majority of cases.

“We believe it is possible that chronic inflammation in some people could be responsible for the neurological symptoms often observed in long COVID,” says Christian Conrad. To investigate this hypothesis further, the research team is now planning to investigate the molecular signatures in the cerebrospinal fluid of long-COVID patients in more detail.

*Radke J et al. Proteomic and transcriptomic profiling of brainstem, cerebellum, and olfactory tissues in early- and late-phase COVID-19. Nat Neurosci 2024 Feb 16. doi: 10.1038/s41593-024-01573-y

About the study

The prerequisite for the study was the explicit consent of the patients or their relatives, for which the research group would like to express its gratitude. The work was carried out as part of the National Autopsy Network (NATON), a research infrastructure of the Network of University Medicine (NUM) funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). The NUM was initiated and is coordinated by Charité and brings together the strengths of the 36 university hospitals in Germany.

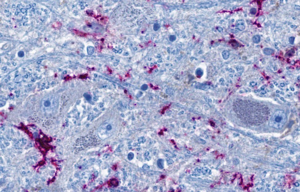

Image: Section of the brain stem: nerve cells (grey-blue) are in close contact with the brain’s own immune cells (purple). The blue thread-like structures are extensions of the nerve cells, which can reach into distant organs as nerve fibres. According to the study, the immune cells and the nerve cells in the brain stem can be directly activated by the inflammation in the lungs via the nerve fibres © Charité | Jenny Meinhardt