The headline “Explain PF Achievements to Your Subjects, GBM Tells Chiefs” in Lusaka Times at first sight looked like it contained a fundamental error.

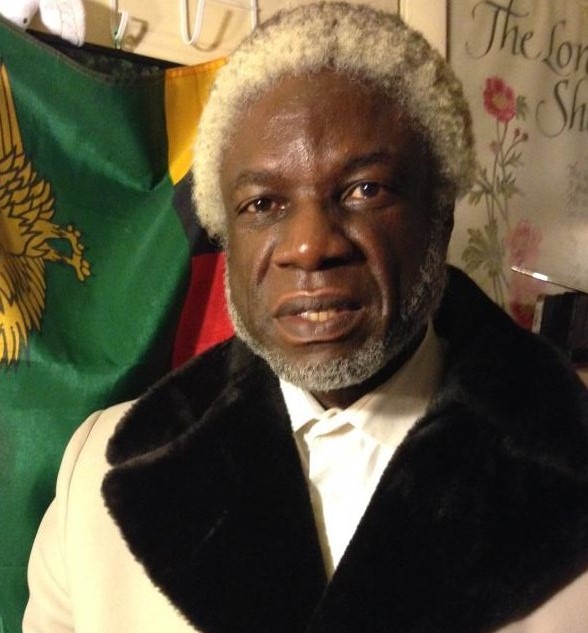

My brother Geoffrey B. Mwamba is a respected and seasoned politician who would be the last person to involve chieftains in partisan politics by using them as PF surrogates, operatives or political cadres.

And how does he expect chieftains to perform such a duty, anyway? Does he expect them to hold political rallies at which they can explain PF’s so-called achievements to their “subjects”?

By the way, Zambians are not “subjects” of chieftains; they are “citizens” of the Republic of Zambia. “Subjects” are people who live in undemocratic nations like Eswatini and Saudi Arabia—people who do not have the right to question how they are governed, for example, and people who do not have the rights and freedoms exercised by citizens of democratic countries like Zambia, such as the freedom I have to openly express my political opinions, and the freedom all citizens have to actively participate in shaping the destiny of our beloved country either directly or through elected representatives.

Since independence in October 1964, there have been complaints and sentiments from some segments of Zambian society about the use of traditional leaders by ruling political parties to gain political advantage, particularly during political campaigns.

There is a need to put an end to the use of chieftains in this manner, because all political parties and their leaders should be received by each and every one of our country’s 283 chieftains as guests in a non-political atmosphere. And, in this regard, political players must refrain from designating any chiefdoms as their “strongholds.”

In 2015, I was impressed by Chief Mumena of the Kaonde people in Solwezi District, North Western Province, who received presidential candidates as guests on their way to districts beyond Solwezi District. That is exactly the kind of posture we should expect from all our country’s chieftains.

If we continue to use chieftains in political campaigns, we could be paving the way for anarchy in our 283 chiefdoms by pushing chieftains into the political arena. We could be planting the seeds of destruction for chiefdoms, the Zambian nation, and for our nascent democracy.

Specifically, chieftains are likely to abuse the absolute traditional authority they wield by imposing their political views and choices on their subjects if government officials and political leaders induce them to participate in partisan politics.

Besides, traditional leaders’ participation in partisan politics does not only have the potential to lead to tribal politics, it can actually lead to bickering and disunity in their chiefdoms.

To digress somewhat, Mr. Mwamba seems to think that the perks, vehicles, bicycles, mealie meal, and other articles of value accorded to chieftains constitute development. Unfortunately, the common people in all the 283 chieftains across the country have continued to experience extraordinary hardships due to PF’s failure to address the fundamental problems facing the country.

A critical shortage of decent public housing, for example, has compelled so many of our fellow citizens to live in shanty townships nationwide; so many of our fellow citizens have no access to electricity and clean water; education and training are not adequately catered for; and the healthcare system cannot meet the basic needs of the majority of citizens mainly due to inadequate medicines, healthcare facilities and healthcare personnel.

Moreover, public infrastructure and services are still deficient, and are mainly dependent on donor-funding; civil servants are still not adequately compensated for their services, and a lot of civil service retirees cannot get their hard-earned benefits on time; and, among many other socioeconomic ills, our country is still experiencing high levels of unemployment.

So, the astonishing poverty which the common people have continued to endure constitutes “development” in brother Mwamba’s mind—it is “Paradise,” to exaggerate a bit.

Unfortunately, Mr. Mwamba and a few other wealthy Zambians, who apparently love their country and its people dearly, live in what the late Joshua Nkomo referred to as “comfort in discomfort” in his speech at the University of Zambia, Great East Road Campus, in 1978.

By “comfort in discomfort,” Mr. Nkomo meant a situation whereby a few citizens who live in luxury in an economically beleaguered country like Zambia are disgruntled and miserable due to the pitiful conditions haunting the majority of their fellow citizens—a situation that, in his view, was confronted by some of his affluent and indigenous political opponents in Zimbabwe who were then part of his country’s oppressive regime.